F1's Technology War: 60 Years of Speed and Innovation

Watching F1, there are moments that make you stop and think. Like when the Lotus 25 first appeared in 1962 and people mocked it saying, "How the hell are they supposed to drive that bathtub-looking thing?" Or when Renault's yellow machine kept breaking down while spewing smoke in 1977, earning the nickname "yellow teapot."

But they were right in the end.

Who the hell changed F1 machines so dramatically, and why? The answer is simple. Engineers' endless technology war.

For over 60 years, F1 hasn't been just car racing. It's been a fierce battlefield where human limits meet the pinnacle of engineering technology. Pure passion for speed drove engineers to pour out ideas that overturned conventional wisdom, while FIA responded with new rules to balance safety and competition.

Looking at this war's history, one fact becomes clear. F1's innovations never just fell from the sky. Every era's breakthroughs emerged from intense struggles to overcome the previous era's limitations. And those innovations created new challenges for the next era.

1960s: British Small Teams' Rebellion

1960 Monza Circuit. Ferrari's massive front-engine machines were claiming their last victory. Nobody knew this was the end of an era.

Cooper's Insane Idea

Britain's small team Cooper's T51 in 1959 was literally revolutionary. They moved the engine behind the driver. Jack Brabham won the championship in this car.

"Why the hell did they do such an insane thing?" The reason was surprisingly practical.

Front-engine cars had a fatal structural flaw. The long, heavy propeller shaft running under the driver's seat forced them to sit high up. This increased the car's frontal area, boosting air resistance. Back then, reducing one square foot of frontal area was equivalent to gaining 25 horsepower, so this was massive loss.

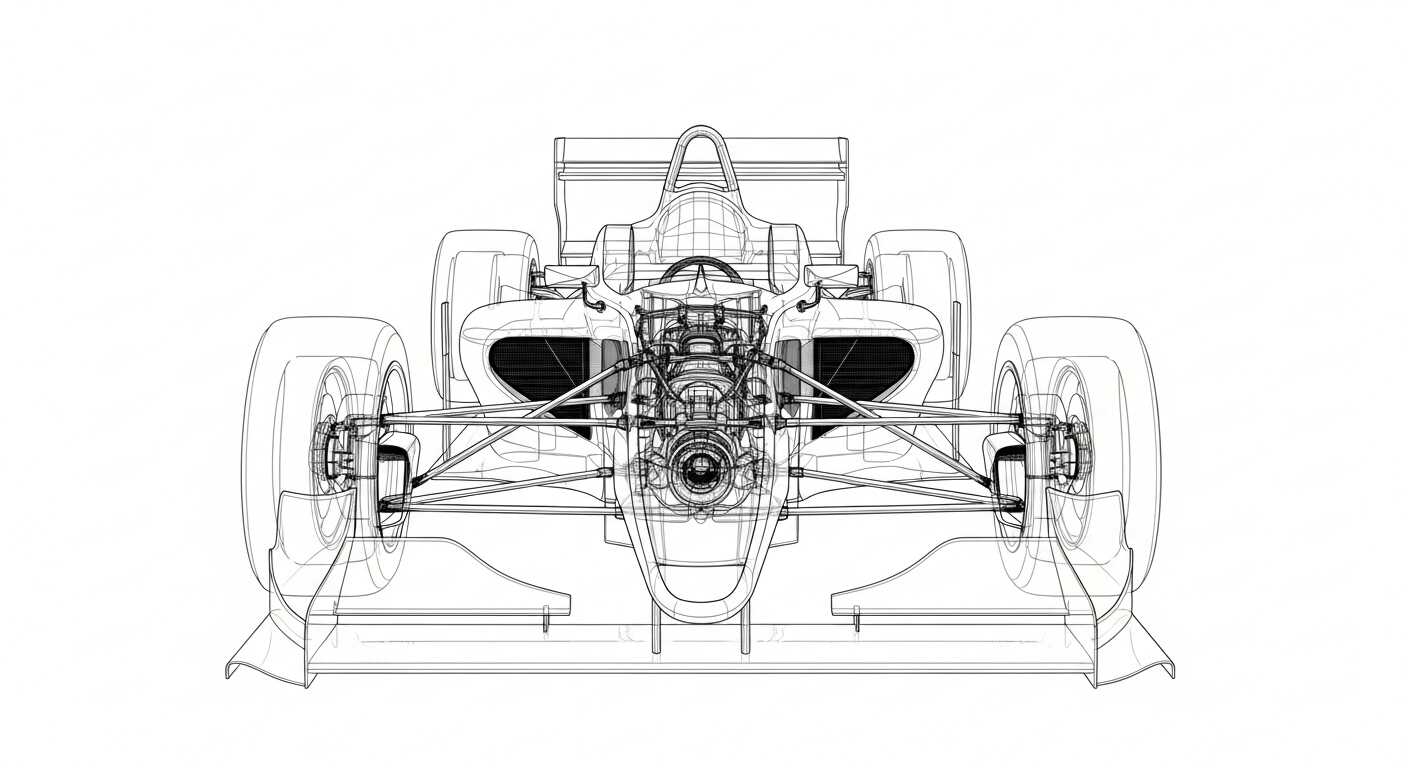

The mid-engine layout solved everything. It concentrated the heaviest components at the vehicle's center of gravity, reducing moment of inertia. Drivers could lie almost flat on the floor, minimizing frontal area. The result was a complete power shift.

Colin Chapman's Bathtub Revolution

If Cooper changed engine position, Lotus's genius Colin Chapman rethought the chassis itself.

When the Lotus 25 appeared in 1962, people were shocked. Instead of the traditional space frame made of welded steel tubes, they brought out a monocoque chassis made of thin aluminum sheets bent and riveted together. The first attempt to bring aircraft technology to F1.

The numbers show the impact. The Lotus 25 chassis had three times the torsional rigidity of previous models but weighed half as much. Total vehicle weight was just 450kg.

Drivers had to sit almost lying down. This earned it the nickname 'bathtub.' But the mockery didn't last long. Jim Clark dominated the 1963 season in this car, winning 7 out of 10 races.

Now F1's two core DNA elements were complete: mid-engine and monocoque chassis. This combination remains F1's basic design philosophy 60 years later.

1970s: War Against the Invisible Enemy - Air

If the 1960s changed vehicle hardware, the 1970s marked the beginning of war against 'air.'

Wings Arrive

When the Lotus 49B appeared in 1968 with huge wings mounted on tall supports, people didn't know what it was. The concept of downforce itself was foreign.

The principle was simple. Flip airplane wings upside down so air flows faster under the bottom surface than the top, creating downward force on the chassis. The moment they realized this force dramatically improved cornering speed by increasing tire grip, F1 entered a new dimension.

Lotus Ground Effect

Wing competition soon evolved in more radical directions. Lotus engineers accidentally discovered during wind tunnel testing that downforce increased dramatically as the vehicle underside got closer to the ground.

What if they made the entire car one giant wing?

The 1978 Lotus 78 and 79 provided the answer. They shaped the sidepod undersides like Venturi tunnels to accelerate airflow and mounted spring-loaded skirts at the bottom to perfectly seal the low-pressure area.

The results were overwhelming. Mario Andretti dominated the 1978 season perfectly in the Lotus 79, becoming champion.

Brabham's Fan Car

Teams falling behind in ground effect had to find their own solutions. Brabham's Gordon Murray's answer was to mount a huge fan at the car's rear to forcibly suck out air.

The BT46B, aka 'Fan Car,' won overwhelmingly at the 1978 Swedish GP. But it disappeared after just one race due to fierce protests from competing teams and political pressure. The most creative yet shortest-lived innovation.

1983 Flat Bottom

Ground effect produced fatal side effects. Cornering speeds exceeded what drivers and circuits could handle. When skirts were damaged, cars instantly lost all downforce, leading to major accidents.

| Year | Monza GP Pole Position Lap Time | Major Events |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | 1:38.080 | Before ground effect |

| 1978 | 1:37.520 | Lotus 79, ground effect mastery |

| 1982 | 1:28.473 | Gilles Villeneuve, Riccardo Paletti deaths |

| 1983 | 1:29.122 | Flat bottom regulations introduced |

After tragic accidents in 1982, FIA finally introduced 'flat bottom' regulations in 1983, forcing car undersides to be flat. They closed Pandora's box.

The real meaning of this era was different. It was the first moment when aerodynamics began overwhelming mechanical grip. All subsequent F1 technological development would revolve around this 'war against air.'

1980s: The Madness of Grenade Engines

When ground effect was banned, engineers had to find new ways to compensate for downforce loss. The answer was turbochargers. But nobody expected this would trigger F1's most insane power war.

Renault's Rocky Pioneering

When France's Renault entered F1 in 1977 with the RS01 featuring a 1.5-liter V6 turbo engine, people couldn't help but chuckle.

Early turbo engines were literally disastrous. Extreme turbo lag meant drivers had to accelerate in advance, predicting corner exit points. Frequent engine blow-ups left white smoke trails as cars stopped. The yellow machine's smoke-spewing appearance earned it the mocking nickname 'yellow teapot.'

But Renault didn't give up. They proved turbo's potential to the world with their historic first victory at the 1979 French Grand Prix.

BMW M12/13: The 1,400hp Monster

As turbo technology matured, F1 entered unlimited power competition. At its peak was BMW's M12/13 engine.

In 1986 qualifying trim, this 1.5-liter 4-cylinder engine produced 1,300-1,400 horsepower at 5.5 bar boost pressure. The most powerful engine in F1 history.

Engineers' approach was brilliant. Instead of new engine blocks, legend says they used cast iron blocks from production cars with over 100,000km. They believed 'aged' blocks that had naturally released internal stress through thermal cycling were more stable than new ones.

Engines running maximum power in qualifying lasted only a few laps. They were called 'grenade engines.' For races, power had to be reduced to around 850hp just to see the finish line.

| Year | Engine | Boost Pressure | Estimated Power | Situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Renault EF1 | - | ~520hp | Turbo era begins |

| 1983 | BMW M12/13 | 3.2bar | ~800hp | Unlimited competition |

| 1986 | BMW M12/13/1 | 5.5bar | 1,300-1,400hp | Peak madness |

| 1988 | Honda RA168E | 2.5bar | ~675hp | Power reduced by regulations |

Living with Turbo Lag

According to 4-time champion Alain Prost, driving in the turbo era was like "taming a monster".

When 1,400hp suddenly hit the rear wheels, tremendous upper body strength and delicate control were needed. Mental pressure from nursing engines that could explode anytime was extreme.

How long could such madness continue?

In 1989, FIA finally banned turbo engines completely. Excessive speeds and astronomical development costs threatened F1's sustainability.

1990s-2010s: Computer Invasion

After turbos disappeared, F1 engineers discovered a new battlefield: electronic control.

Williams' Electronic Magic

The 1992 Williams FW14B looked like something from a science fiction movie. Active suspension used computer-controlled hydraulic actuators to maintain perfect chassis height and attitude in any situation.

Traction control automatically adjusted engine output by detecting rear wheel slip. Nigel Mansell's overwhelming domination of the 1992 season in this car wasn't surprising.

But these technologies faced criticism for skyrocketing development costs and diminishing drivers' roles. Electronic aids were completely banned from 1994 for this reason.

2014 Hybrid Revolution

F1 introduced hybrid power units in 2014, adapting to environmental regulations and the automotive industry's electrification trend. This was a complex system combining a 1.6-liter V6 turbo engine with two energy recovery systems.

Key components included:

- MGU-K: Recovers braking energy as electricity and provides additional 161hp during acceleration

- MGU-H: Recovers thermal energy from turbocharger exhaust and plays a key role in eliminating turbo lag

- ES: Lithium-ion battery storing recovered energy

This system achieved the remarkable feat of producing nearly 1,000hp while improving fuel efficiency by over 30%.

2026: Dawn of a New War

F1 faces another massive change in 2026, simultaneously pursuing sustainability and thrilling racing.

MGU-H's Exit

The biggest change is complete removal of MGU-H. Eliminating this extremely complex and expensive system allows new manufacturers like Audi and Ford to enter.

Instead, MGU-K output increases roughly threefold from 120kW to 350kW. The ratio between internal combustion engine and electric motor in total output rebalances to nearly 50:50.

| Category | 2014-2025 | 2026 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICE Output | ~560kW | ~400kW | Decrease |

| MGU-K Output | 120kW | 350kW | 300% increase |

| Electric Ratio | ~15% | 50% | Dramatic increase |

| Fuel | 10% bio | 100% sustainable | Complete carbon neutral |

Active Aero's Revival

Interestingly, active aerodynamics banned in 1994 returns after 30 years. Variable systems that fold wings on straights to reduce drag and raise them in corners for downforce.

Manual override mode is also introduced, allowing drivers to use additional electric output momentarily by pressing a button. Like a 'booster' in video games.

The Never-Ending War

Looking back at F1's 60+ year technology war reveals a clear pattern. Every innovation started from attempts to overcome the previous era's limitations.

1960s mid-engine and monocoque overcame front-engine limitations. 1970s aerodynamics transcended pure mechanical grip limits. 1980s turbos compensated for downforce loss from ground effect bans. 2014 hybrids responded to new environmental regulations.

And 2026 regulations? An attempt to solve the 21st century contradiction between sustainability and competitiveness.

Honestly, this technology war will never end. It shouldn't end. That's what makes F1 F1.

What will the next chapter created by 2026's new F1 look like? Will the era of perfect harmony between electric and combustion engines become another innovation starting point, or a turning point toward complete electrification?

One thing's certain: engineers' all-nighters to find that answer have already begun.